Using ISAs to Build Racial Equity in Higher Education

July 12, 2020

By Ali Fredman

Higher education has received a great deal of credit as a social and economic equalizer in American society.

In reality, substantial disparities in education financing, resources, and outcomes continue to undermine access, inclusion, and equity in higher education.

Wealth disparities in minority communities have made student loans both a more crucial and, by the same token, more unforgiving gateway to higher education access and professional achievement for students of color.

Among college graduates, the average Black borrower has $7,000 more in education debt than White peers. There are myriad systemic factors that account for Black students’ heavier debt burden, each with deep historical roots. Intergenerational wealth gaps, vast disparities in quality of K-12 education and college advising, and targeted college admissions all play a role in differential higher education experiences for black students. In turn, each of these factors is compounded by funding gaps and student finance dynamics that disproportionately affect students of color.

Income Share Agreements (ISAs) can help to address these funding gaps. ISAs are an innovative higher education financing tool that links students’ payments to their earnings.

Unlike student loans, ISAs do not have an outstanding balance or interest rate, meaning that the potential for the financial obligation to balloon due to deferment is eliminated. Borrowers only make payments if their income is above a certain threshold, and the total repayment amount they must pay back is capped. As a result, the flexible payments and insurance-like characteristics of ISAs offset the most punitive characteristics of traditional student loans, offering an opportunity to break the cycle of intergenerational wealth disparities and their role in higher education access.

Disproportionate financial barriers influence Black students’ choice of school, their degree rates, and eventually their rates of financial stress and default.

Students of color are less likely to attend elite colleges and more likely to attend schools with less funding, lower graduation rates, and worse labor market outcomes.

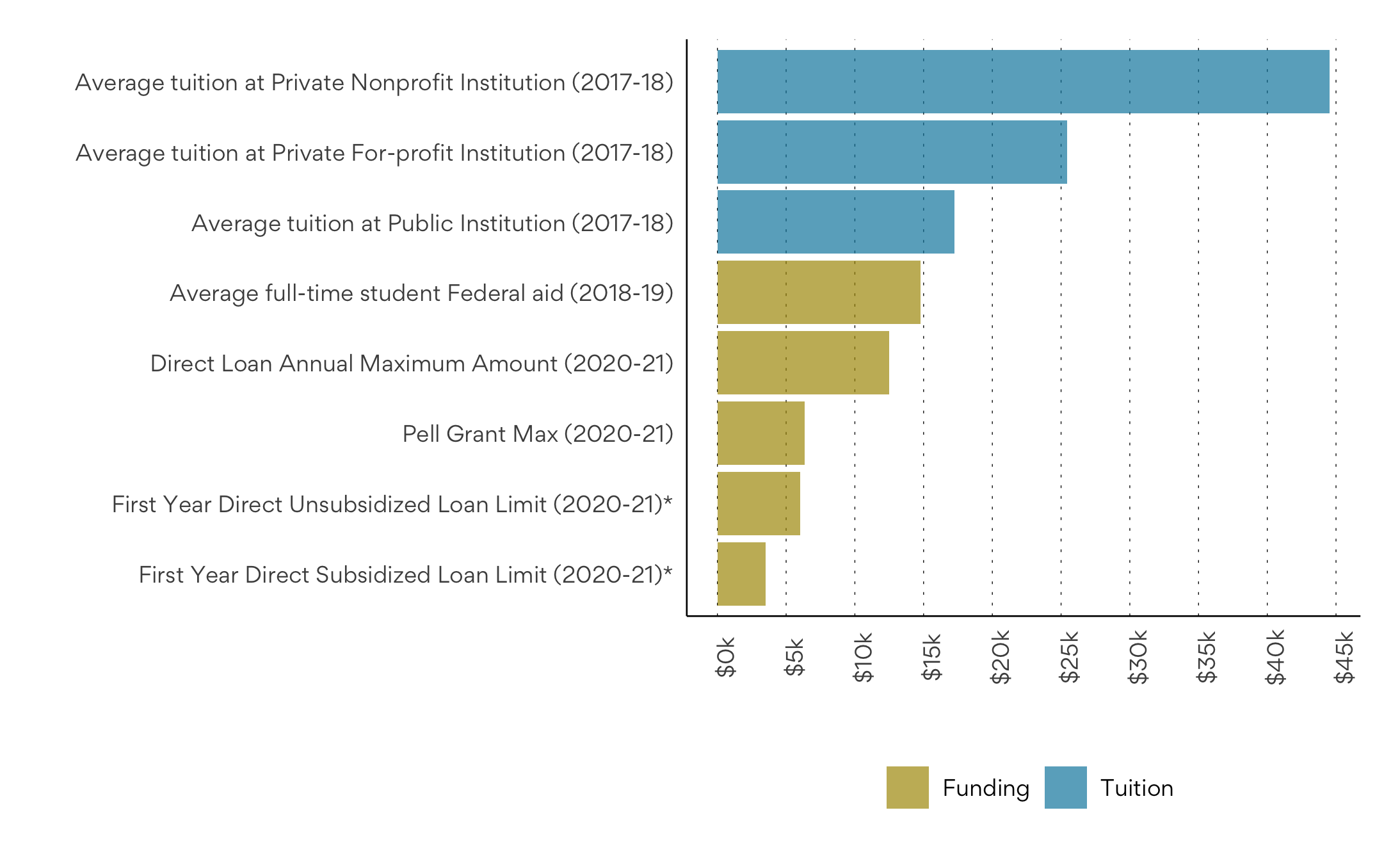

According to researchers, only 7% of the students attending the 450-plus best-funded and most selective four-year colleges are Black, while enrollment in the 3,000-plus least well-funded two- and four-year colleges is 20% Black1https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/SeparateUnequal.FR_.pdf. At the same time, as the chart below indicates, federal support for low-income students, such as Pell Grants and Direct Loan limits are insufficient to cover rising costs at public 4-year institutions, not to mention elite private schools.

Higher Education Funding Gap: Public financing falls short of tuition needs

Source: U.S. Department of Education and CollegeBoard

In order to complete a 4-year degree–and enjoy its well-documented lifetime benefits–a disproportionate number of students of color must risk additional debt.

Anecdotally, we know that many students facing funding gaps opt to attend community college or forego higher education completely, rather than take out private loans to cover costs. By contrast, ISAs link financial obligation to success after graduation, de-risk not only the decision to pursue higher education, but also at which price point and type of institution.

Black students are more likely to attend for-profit colleges than public colleges, representing 21% and 13% of the student body respectively.

This is the result of both targeted marketing by for-profits and the failure of the non-profit higher education system to recruit and provide ample financial aid and guidance to students from high schools where the majority of students are people of color. While for-profit colleges play an important role in boosting higher education access in underserved communities, graduates’ career outcomes and professional attainment vary widely across for-profit programs.

Significantly, students at for-profit colleges, and students of color in particular, have the highest dropout rates and worst experiences with student debt. More than half – 53% – of borrowers at 4-year for-profit programs do not graduate, including a majority of Black and Hispanic borrowers. Contrastingly, 20% of borrowers at public 4-year colleges and 33% of community colleges drop out. In turn, failing to complete a degree is correlated with an increased risk of default in addition to decreased opportunities for social mobility.

ISAs introduce a mechanism that encourages schools to invest in students of color and their professional careers.

ISAs force schools to demonstrate that their product leads to successful student outcomes, thus creating an accountability that is key to addressing racial gaps in educational attainment and benefits.

Higher education financing has conventionally placed an undue burden on students who bear substantial debt and the risk of default. Students of color not only face an uncertain labor market, but also one that is rife with the pitfalls of structural racism.

ISAs are an opportunity to shift risk away from students and to offset the consequences of inequities and access in career development.

Furthermore, for investors and schools, adopting flexible financing promotes inclusive workforce development and higher education attainment among Black students, with benefits that can be shared through society.